Integral calculus is in many ways, complementary to differential calculus.

In integral calculus, instead of describing small changes with respect to something (like we do in differential calculus), we add up multiple small changes to get the total change in something.

In differential calculus, we were interested to know how something, such as the position of an object changes in relation to another quantity, such as time. The key was that we would look at “small changes” in that something at each instant of time.

In contrast, when we talk about integral calculus, we’re specifically interested in knowing the total change in something over a specific interval, not just at a single point.

So, you should really think of integral calculus and differential calculus as complementary to one another; differential calculus is concerned with local changes, while integral calculus is concerned with global changes and depending on the situation, we may be interested in either one.

Now, similarly to how in differential calculus everything was based on the concept of a derivative, in integral calculus, the central idea is the notion of an integral.

Introduction To Integrals

Simply put, an integral is a mathematical tool for “adding up” lots of small pieces. Now, while this may sound a little vague without an example, this is really the key underlying idea behind what an integral is. So, always keep this in mind; integral=”sum of lots of small stuff”.

To motivate the idea of an integral, consider the stuff we talked about in the last lesson. In particular, how the velocity of an object could be described as the time derivative of the object’s position:

I’m now going to do something that a mathematician may not like very much; multiply by dt on both sides:

Here we essentially have a small displacement in position (that’s what the dx represents) being equal to the velocity at that “instant” of time multiplied by a small time interval (dt). So, this is a small displacement during a small time interval.

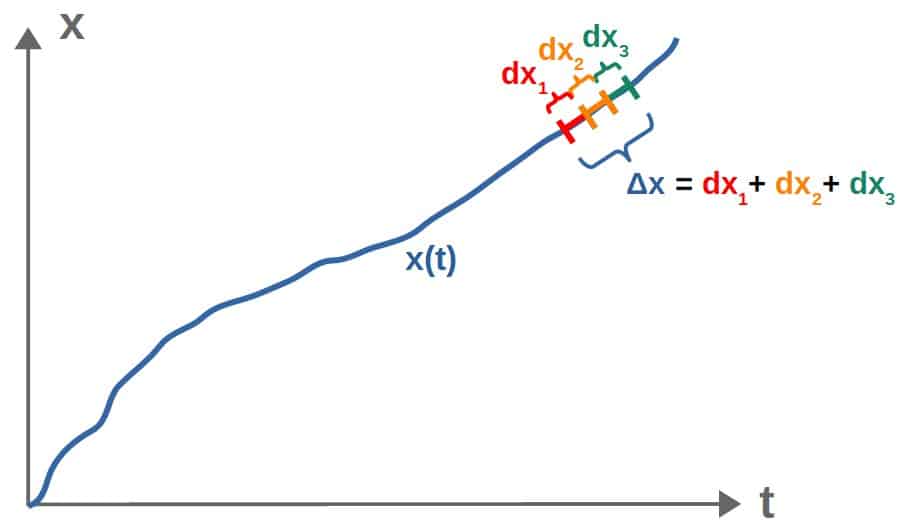

Now, what if we do this at each point along the trajectory of an object?

In other words, we “divide” the total trajectory, (i.e. the curve described by x(t)) into really small pieces (each piece given by dx=v(t)dt) and then add up all of these pieces. We would then get the total displacement Δx along the trajectory, at least approximately (depending on how small these pieces are):

Each of these dx-pieces are going to be the velocity at that “instant” of time (if we imagine these pieces to be really small, then it makes sense to talk about an “instant of time”) multiplied by the little time interval dt, in which that little displacement dx occurs in.

So, this can be written as:

In general, we could take as many of these pieces as we wish along this trajectory, so we could write this as a sum of i terms (the index i being i=1,2,3… up to however many pieces we break the trajectory into):

Now, here comes the bit where calculus comes in (so far we’ve just been adding together a bunch of displacements); imagine that each of these pieces dti is infinitesimally small.

In this case, our expression of the total displacement as the “sum of many little displacements” becomes exact; the smaller each “displacement piece” is, the more accurate the result is going to be and since we’re now adding up infinitely many infinitely small pieces, the result is exact.

In practice, this now becomes an infinite sum and each piece we’re summing over is the velocity at that exact instant, v(t), multiplied by an infinitesimal time interval, dt.

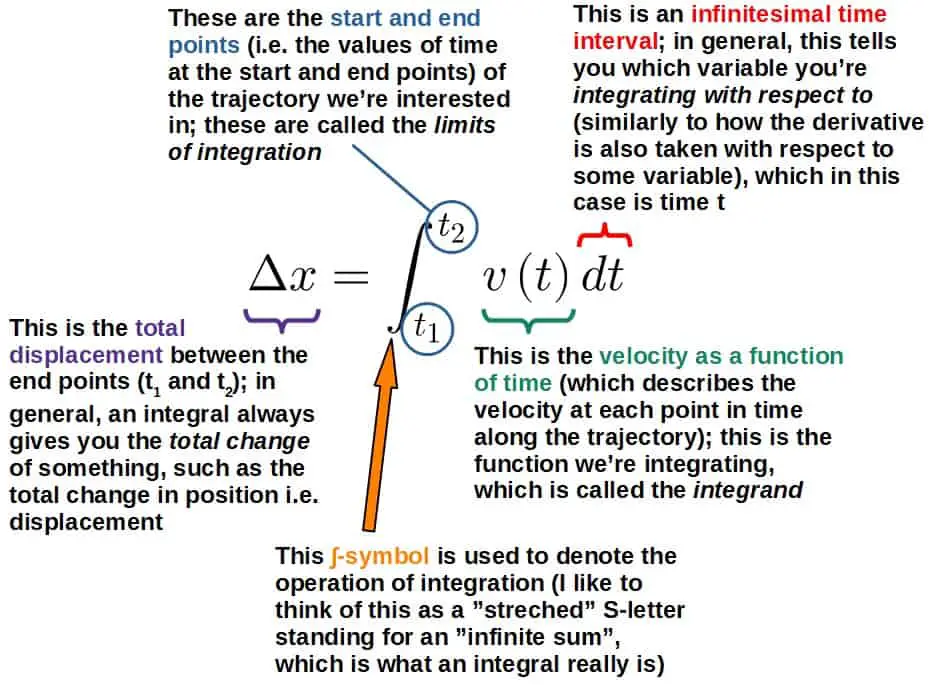

Well, there’s a name for this kind of an “infinite sum of infinitesimal pieces” and it’s called an integral:

This is the exact formula for the displacement (even if the velocity is not constant, but a general function of time). Later, we’ll see how to actually calculate these integrals.

However, before doing that, let’s look at what each of these symbols here really mean:

Now, similarly to a derivative, an integral is also a mathematical operation that has certain rules we can use to calculate stuff.

Also, we do not necessarily have to specify what the limits of integration are, in which case the result of the integration gives us a function (in our case, the position as a function of time, x(t)) instead of just a number (which is what the displacement would be):

This is called an indefinite integral. We’ll discuss these more soon.

Sidenote; the concept of an integral is often introduced as describing the "area under the curve of a function", however, I personally don't think this is the best way to think about integrals. Really, all an integral fundamentally is is a sum of lots of small pieces. Sometimes this may describe the "area under a curve", but often it's going to describe something completely different, which is why it's better to think of the concept of integration more generally right from the start. The way we've discussed integrals in this lesson is the general way to think about an integral and this idea of an integral as a sum of small stuff is easy to apply to pretty much everything.

An integral is really just a sum of infinitely many infinitely small pieces that together add up to something finite.

How To Calculate Integrals: Basic Rules

To answer the question of how to calculate integrals, we first have to think of what an integral really represents; the total “sum” of many small changes.

If we think of these small changes as represented by the derivative of a function at each point, then adding up all of these small changes (integrating) should give you the total change in the function itself (similarly to how integrating the velocity, dx/dt, gave us the total displacement Δx).

Therefore mathematically speaking, the operation of taking an integral is equivalent to asking the question; what function is the integrand a derivative of? So, in a sense, the integral calculates the anti-derivative of a function.

We’ll discuss this in more detail later, but this is generally speaking the mathematical process of what calculating an integral means.

As an example, let’s say we want to integrate the function t2 (with respect to the variable t):

All we have to do is ask; what function is t2 a derivative of? Well, one choice would be t3/3. This can be seen quite easily from just taking the derivative of this:

So, the result of the integral is then:

Now, in practice, when we’re calculating integrals, we do not have to really think about them and “guess” the answer like we did here; there are lots of useful rules for doing these integrals just as pure calculational operations.

However, the main idea behind every one of these rules is the question of which function will taking the derivative of give you back the integrand (the function you’re integrating), i.e. what the anti-derivative of the integrand is.

Sum Rule

The sum rule for integrals states that the integral of a sum of two functions is just the sum of the integrals of these functions separately (equivalently to how this is also true for derivatives):

Also, similarly as when taking a derivative, we can also pull out any constants outside of the integral:

Power Rule

The power rule of integration is essentially the “reverse operation” of the power rule for taking derivatives.

This rule states that the integral of any function with a constant exponent (so of the form tn, where n can be any number except -1) is given by the formula:

In contrast, the power rule for derivatives reduced the exponent by 1, while this increases the exponent by 1. Now, if we want to verify why exactly this rule works, we can simply just look at whether the derivative of this would give us back the integrand, which it does indeed:

As an example, let’s say we want to calculate the following integral:

First of all, since this is a sum of terms, we can use the sum rule for integrals to write this as:

We can then pull out these constants:

Okay, let’s look at each of these terms separately. For the first integral, we have t4, meaning that the exponent is n=4. We can use the power rule for this to get:

For the second integral, we similarly get (also don’t forget the factor of 3):

Now, the last term is a little funny since we have an integral of just dt:

What does it mean to integrate just dt? Well, here our integrand is simply 1, which we can always write as t0 (since anything to the zeroth power is 1):

Here we simply have another integrand of the form tn with n=0. We can apply the power rule here to get:

Now, putting together all of these, we have:

This is then the answer to our problem:

Product Rule (Integration By Parts)

The product rule for integrals is slightly more complicated than the product rule for derivatives.

Moreover, the product rule for integrals is usually called integration by parts (although integration by parts is usually written in a slightly different way) and it states that we can write the integral of the product of two functions as:

Here we essentially have an integral inside an integral, but this really isn’t anything difficult; you simply just calculate the integral of g(t) first and then integrate that resulting function with this df(t)/dt.

Let’s look at a nice example of where this integration by parts technique works very well. In particular, let’s calculate the following integral:

Since this is a product of two functions, we can use the integration by parts -formula. Let’s define our functions f(t) and g(t):

We can then apply integration by parts:

Inserting the functions, we get:

This may look complicated, but there is a nice “trick” we can do, which you’ll see soon. First, however, we need to use the fact that the integral of sin(t) is -cos(t). You can verify this easily by differentiating -cos(t) or you can take a look at the list of integration formulas below.

Anyway, we have the following:

We can apply this to both of the two terms on the right-hand side, giving us:

Let’s now take the derivative of cos(t), which gives us -sin(t). See the formulas in the last lesson for this. This then gives us:

Well, what do we do now? We have the same integral on the right, which we of course don’t know the answer to yet.

Here’s the simple “trick”; just move this term to the left-hand side:

Now we simply have the sum of two of the same terms, which gives us twice this integral:

Now all we do is divide by two and get the answer to our problem:

Hopefully this illustrates the use of this integration by parts -technique. Simply put, you can use this whenever you have an integral of a product of two functions and sometimes you’ll be able to simplify the result.

Now, for integrals, there isn’t a general rule for composite functions like there is the chain rule for derivatives. The closest to such a rule is an “integration trick” usually called u-substitution.

Definite vs Indefinite Integrals

Before we discuss u-substitution, however, we need to discuss the differences between a definite integral and an indefinite integral. We’ll also touch on boundary conditions for single-variable integrals.

Indefinite Integrals & Boundary Conditions

An indefinite integral is an integral with no specified integration limits. Indefinite integrals generally give you another function:

These indefinite integrals are what we calculated in the examples earlier. The function that this kind of integral produces is the answer to the question “what function is the thing I’m trying to integrate the derivative of?”.

Now, there is a little problem here; the derivative of any constant is zero. Therefore, we can always add a constant to the answer of any indefinite integral and it’ll still be the correct answer.

For example, consider the following integral again:

If we add a constant C to the answer on the right-hand side and take its derivative, we still get the function t2, as we should:

Therefore, the general answer to the above integral is actually t3/3 plus ANY constant:

This constant is often called an integration constant and generally speaking, you have to add one to each indefinite integral you do. So, in all of the examples from earlier, you should take the correct answer and add a constant to those answers to get the general solution.

Now, how do you know what this constant should be? The answer is that you should specify a boundary condition, which will often be the value of the function at t=0 (for example, in physics this may represent the initial position of an object at time t=0).

This boundary condition specifies what the value of the constant should be, so that you get a unique answer to the integral (specific to that boundary condition). If you don’t have a boundary condition, you can only determine the answer to your integral up to an arbitrary constant.

For this example, we’ll imagine some object moving with constant acceleration in 1D in the x-direction (along the x-axis).

Let’s say we have a velocity of the object being described by the following function of time:

We also have a boundary condition that the object begins moving from the origin. In other words, its position x(t) at time t=0 is zero:

We now want to find the position of the object as a function of time (and then see what the boundary condition does for us). To do this, we simply take the indefinite integral of the velocity:

Now we just apply the power rule to both of these terms, giving us:

Now, we have to add an arbitrary constant to get the general answer (the position x(t)) to our problem:

So, this is the general answer to any position as a function of time with constant acceleration.

To get the unique answer to our specific problem where the object starts from the origin, we apply the boundary condition (i.e. plug in t=0, which should be x(0)=0 according to our boundary condition):

This, of course, gives us just:

So, with this boundary condition, we get that the integration constant should be zero. Therefore, the answer to this problem with this specific boundary condition is:

Now, the importance of a boundary condition is that it gives us a unique answer to a specific problem we may want to solve; it’s no use solving an integral to get a general solution to something if we need one specific solution. This is where you need to specify a boundary condition.

Boundary conditions are also used to get specific solutions to differential equations (which we won’t need much in this course, except Poisson’s equation briefly later on; Maxwell’s equations are also differential equations, but we won’t really need any differential equation solving strategies for them in this course).

A differential equation is essentially an equation that involves derivatives of some function you want to solve for.

The amount of boundary conditions for an ordinary differential equation is the same as the “order” of the highest derivative in the equation (so, a DE with second derivatives would actually need two different boundary conditions; this comes from the fact that these are generally solved by performing two integrals on the same function).

We can also have partial differential equations, which as the name may suggest, involve partial derivatives (these will be explained in great detail later on). With a PDE, the boundary conditions can actually be whole functions, not just constants.

Anyway, the main point is that to get a unique answer to an indefinite integral, you have to specify a boundary condition. If you don’t specify a certain boundary condition, you get the general answer to an indefinite integral with an arbitrary integration constant.

Definite Integrals & Integration Limits

A definite integral is an integral where the integration limits are specified in advance.

A definite integral will generally give you just a number (unless your integration limits themselves happen to be functions). Well, what number? I’m going to call that number ΔF, you’ll see why soon:

So, here we’re integrating the function f(t) between the points a and b (which are the integration limits in this case) and this results in a number ΔF.

Now, what exactly does this mean? To do a definite integral, you just do the integral just like you would do an indefinite integral; use the various integration rules to get some function.

However, once you get the function that is the answer to your integral, you then plug in the integration limits to that function.

For example, consider the function t2 again. We’re now taking a definite integral of this between the values t=a and t=b:

To do this definite integral, we just integrate t2 to give us t3/3. However, this is not the answer yet, since this is a definite integral. We also have to substitute the integration limits into this, which we denote in the following way:

Now, what does it mean to substitute these integration limits? Essentially, you plug in t=b, the “end point” of the integration, to this function first and then subtract the function with the value t=a, the “start point”:

That’s the answer to our definite integral (note that this is just a constant number, since both a and b are just some numbers):

In general, to calculate any definite integral, you first calculate the function F(t) that you’d get if you were doing an indefinite integral and then you plug into that the integration limits (a and b) by taking the difference of the function F(t) at these points:

Also, note that in general, this F(t)-function that is the answer to the integral (i.e. “anti-derivative” of f(t)) is going to contain some arbitrary integration constant.

However, since we’re doing a definite integral and taking the difference of F(t) at the boundaries of integration, this constant plays no role as it will just cancel out:

So, from a definite integral, you always get the same number as an answer regardless of what arbitrary integration constant you may have. That’s why the integration constants are just left out completely when doing definite integrals.

Definite integrals also have plenty of applications in physics, particularly in situations where we want to calculate a change in something between certain points.

As an example, consider again the following velocity of an object as a function of time:

If we want to find the distance d an object moves during some time interval (with the starting time being t0 and the final time T), we can integrate this velocity as a definite integral from t=t0 to t=T:

This just gives us the same thing we had in the earlier example, but we now have to also substitute in the integration limits:

We now plug in these limits, which gives us the thing inside the parentheses evaluated at t=T minus the thing in the parentheses at t=t0:

We can write this in the following form (by factoring out common terms):

This is the formula for the distance an object would move under constant acceleration between the time t0 and T.

As a numerical example, we could say that the object is under a constant acceleration of a=10 m/s2 and it starts with an initial velocity v0=15 m/s. The distance it would then move in 5 seconds (for example, between the times t0=5 s and T=10 s, which is a 5-second interval) is:

Also, note that for a definite integral, the answer generally only depends on the end points (the integration limits).

In other words, when doing definite integrals, the answer will depend on the boundaries of the region you’re integrating over. This idea will turn out to be much deeper and more general once we get to Stokes’ theorem and the divergence theorem.

Useful Tricks For Calculating Integrals

In this section, I’ll cover some of the most common and most useful tricks you can apply when you have an integral that you can’t necessarily calculate directly with any of the basic integration rules we covered above.

Integration By Parts

We covered this “trick” already earlier, but just to recap, you can apply this whenever you have an integral of the product of two functions.

In that case, you can use the following formula:

Note, however, that this may or may not simplify your calculations.

Just like with any of these integration tricks, it’s going to take some practice and experience with doing various integrals to recognize which kinds of integrals will integration by parts be useful for.

U-Substitution

The technique commonly called u-substitution is probably the most useful and generally most applicable integration trick you’ll use.

This technique is going to be most useful when you’re integrating a composite function of some sorts (i.e. a function inside another function) that you don’t necessarily know how to integrate in that specific form.

Specifically, u-substitution works if you have an integral of the form:

In other words, the integral of the product of some composite function and the derivative of the “inner function”. While this may seem very specific, you’d actually be surprised how many integrals can be solved using this technique.

Essentially, u-substitution consists of the following steps:

- Arrange the integral such that it is in the form:

- Identify what your f(t) and g(t) are.

- Make the substitution u=f(t), such that the integral becomes:

- Calculate this integral with respect to the variable u. Hopefully you now have a much simpler integral, which is just an integral over a single function.

- As a result from the previous step, you should now have some function of u. Now substitute back u=f(t) into this function and you have the answer. Don’t forget the integration constant!

Now, the tricky part with u-substitution is often with identifying the functions f(t) and g(t) and choosing which function to make the u-substitution, u=f(t), on. The only way to get familiar with this is to just do lots of practice problems (which you’ll find in the workbook)!

Let’s solve the following integral:

The easiest way to do this is with u-substitution. The first thing to do is arrange this into the form:

Well, one way to do this is by choosing g(t)=et and f(t)=t2, in which case:

We can therefore write the integral in the following form:

This is now exactly in the form we want (with df(t)/dt=2t and g(f(t))=et2). We can now make our u-substitution:

Our integral then becomes:

The integral of eu is simply just eu (you can check this from the formula list down below), so we get:

Now one last thing; u here is just a “dummy variable”, which we only use to solve the integral. What we’re really interested in is the function in terms of our original variable t.

So, we simply just substitute back the definition of u from earlier:

This is now the answer to our original integral:

One more noteworthy point about u-substitution is that if you have a definite integral, you also have to change the integration limits accordingly when performing a u-substitution.

In other words, you originally have some integration limits for the t-variable, a and b, and after you make the u-substitution, you’ll have some other integration limits for the u-variable, namely the value of u at these limits, u(a) and u(b).

So, for a definite integral, the u-substitution “formula” would essentially become:

You’ll see a more concrete example of how to actually change these limits of integration in the example on doing a trigonometric substitution (which is a “different form” of doing a u-substitution).

Trigonometric Substitution

Trigonometric substitution (or “trig substitution” in short) is another substitution method you can use to solve an integral if no other methods work well.

When doing a trig substitution, you essentially substitute a trigonometric function in place of some part of your integral.

Sometimes, if no other methods (such as u-substitution or integration by parts) work, this may allow you to turn your integral into a simpler integral over just a single trigonometric function that you can then integrate fairly easily.

The steps for calculating an integral using trigonometric substitution are more or less as follows:

- Identify what part of your integral you could substitute with a trigonometric function (of the variable u). This often works well for a term which is of the form of a square root of some function.

- Calculate the derivative dt/du and solve for dt in terms of du (simply by multiplying in a very non-rigorous way). You’ll need this to turn the integral with respect to t to be completely with respect to u.

- Simplify the integral. You’ll often need some trigonometric identities and formulas for this.

- You should now have an integral completely in terms of the variable u, if everything is done correctly. Calculate the integral.

- You should get some function of u as a result (for indefinite integrals). Now substitute back in the function u in terms of t to get your answer in terms of the variable t.

Below, you’ll find an example of how these steps are done in practice.

As an example, let’s do the following integral:

Now, you could try the standard u-substitution for this, but it’s not going to work as this is not in the correct form for a u-substitution.

The simplest way to solve this would be with a trigonometric substitution in which we replace a part of this integrand with some appropriate trigonometric function.

In particular, let’s do the following substitution:

Now, while this may perhaps seem totally random and arbitrary, we’ll see that this substitution actually simplifies our integral a lot.

Note, however, that since we’re switching from the t-variable to a new u-variable, we also need the differential dt replaced by du in order to actually do the integral with respect to u.

To do this, we take the derivative of t with respect to u:

We’ll now do something that may seem weird; multiply by du to solve for dt. We then get the differential dt in terms of du:

Okay, we now have the integrand in terms of u as well as the dt-piece in terms of du.

Now we still need to figure out what the limits of integration change to since we’re doing the integral over u (note that you only have to do this for definite integrals).

The original integration limits were 0 and 1. We can change these to the u-limits by looking at our t in terms of u again:

We can simply plug in the first limit, t=0, and solve for what u has to be:

Doing the same for the other limit, t=1, we get:

So, our integration limits for the u-integral are 0 and π/6.

We can now plug in all of our pieces (t=2sin(u), dt=2cos(u)du and the integration limits) to get the integral over u:

This can be simplified a lot:

This is now an incredibly simple integral to do; we just get u as a result and then substitute in the integration limits:

This is indeed the correct answer to our definite integral (which we were only able to solve using trigonometric substitution):

Below I’ve included a table of the most common expressions you may want to use trigonometric substitutions for. Note, however, that these are not the only expressions you can use trig substitutions for.

I’ve also included which trigonometric and identities functions you should use as well as what the differential dt is going to be using this substitution. You can use this table as a helpful tool when you’re calculating integrals by yourself

| Expression (a = some constant) | Trigonometric Substitution (t in terms of u) | Differential (dt in terms of du) | Trigonometric Identity (for simplifying) |

|---|---|---|---|

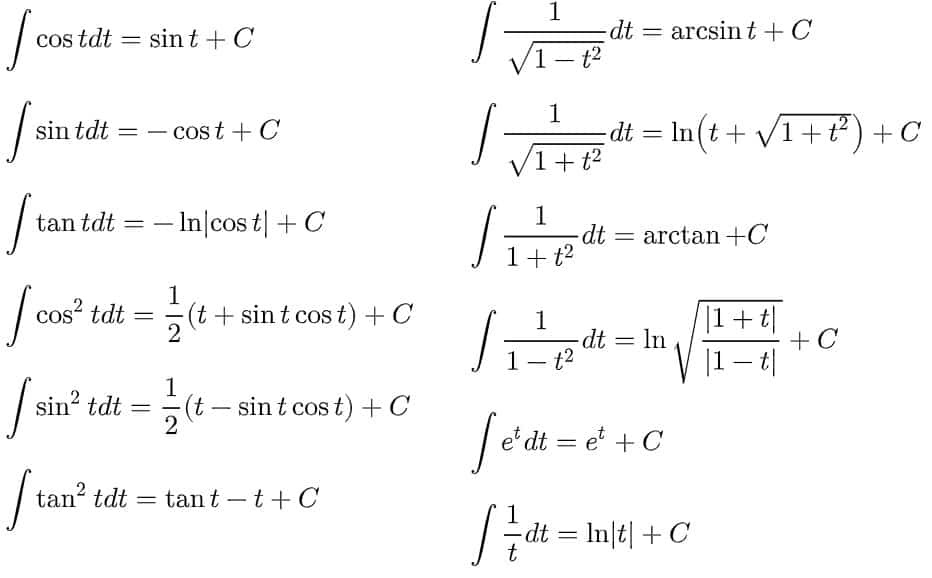

List of Integration Formulas

Below is a list of some integrals that you may encounter:

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

The fundamental theorem of calculus is essentially a theorem that relates derivatives and integrals.

One way to express this theorem is to say that integrating the derivative of any function gives you the function itself (up to an integration constant):

Intuitively, we can understand this as basically saying that “adding up” (integrating) lots of small changes (derivatives) in a function gives you the function itself.

Equivalently, we could also say that differentiating the integral of some function also gives you the function itself:

At first sight, the fundamental theorem of calculus may seem to just state that integrals and derivatives are opposite operations and “cancel out” one another.

Now, while this interpretation works fine for single-variable integrals, it really isn’t the best way to think about the fundamental theorem of calculus. This is because this interpretation does not quite generalize when we get to integrals in 2D, 3D and even higher dimensions.

In my opinion, a more general interpretation comes from the fundamental theorem of calculus applied to definite integrals, which states the following:

What this really states is that adding up lots of small changes in a function over some region (between the end points a and b) gives you the total change in the function at the boundaries of the region you’re integrating over.

Or a more mathematical way of stating this would be that integrating the derivative of a function over a region is equivalent to the total change in the function at the boundaries of that region.

Now, you may not appreciate the importance of this interpretation yet, but once we get to Stokes’ theorem and the divergence theorem later in this course, you’ll be able to see exactly why we want to think about the fundamental theorem of calculus in this way.

In practice, it’s completely valid and often useful to treat integrals and derivatives as “opposites” of one another when dealing with single-variable integrals. You’ll see how this can be used in the example below.

However, you have to be careful of how you generalize this idea to work if you’re dealing with integrals of two or more variables.

The fundamental theorem of calculus is extremely useful and easy to use if we want to “undo” a derivative in one dimension.

For example, consider the definition of acceleration as the second time derivative of position (in one dimension):

Our goal is to basically solve for the function x(t) here, which means that we have to “undo” two of these time derivatives.

Now, we can also write this in terms of the first time derivative of velocity:

We can now integrate both sides of this with respect to t:

Now, by the fundamental theorem of calculus, since we’re integrating the derivative of v(t) on the left-hand side here, we should just get v(t) itself:

On the right-hand side, we can just integrate the constant a to get at+C:

So, we’ve then solved for the velocity as a function of time:

Now, this constant C corresponds to the value of v(t) at time t=0, which is just the initial velocity that I’ll label v0:

But we also know that velocity is the time derivative of position, so we can write this as:

We an again integrate both sides, which gives us the function x(t) on the left-hand side (by the fundamental theorem of calculus). We then get:

So, just to recap, we’ve essentially used the fundamental theorem of calculus to solve for the position as a function of time from the definition of constant acceleration:

In general, this thing we just “solved” is a differential equation (of second order since it contains a second derivative). The fundamental theorem of calculus is essentially used as the basis of solving any differential equation of one variable and you’ll come across this in pretty much ALL of physics.

We could even use the fundamental theorem of calculus to solve an equation of the form (for the function x(t)):

We can again write the acceleration term (second derivative of position, d2x(t)/dt2) as the time derivative of velocity:

We can then integrate both sides and apply the fundamental theorem of calculus:

Let’s now express the velocity as the time derivative of position:

Now, we can’t directly just integrate this to solve for x(t). Instead, we’ll subtract -bx(t) from both sides and then divide by C-bx(t), which gives us:

We can now do something that may seem a bit random, but this is actually done quite often to solve differential equations; we’ll do a u-substitution of the form:

The reason this is useful is because it allows us to greatly simplify our equation so that the fundamental theorem of calculus can be applied easily. Anyway, if we now calculate the derivative du/dt, we get the following:

We can now insert this into the equation from above:

Multiplying by -b, we get this into the nice form:

Now all we do is integrate both sides with respect to t and apply the fundamental theorem of calculus:

Let’s now substitute back into this the definition of our u-variable from earlier, giving us:

We can easily solve this for x(t) by basically exponentiating both sides:

We can write the exponential term in the following form:

Now, since C and D are totally arbitrary integration constants, I’ll just relabel them as:

Doing this, we get:

So, our solution x(t) to the equation is just:

Now, if this example seemed complicated, the key point with all of this is that we can essentially solve differential equations of one variable (equations that contain derivatives) by using the fundamental theorem of calculus.

You’ll find that this is especially useful in physics, such as when solving Newton’s second law (F=ma), which is really a differential equation for the position as a function of time:

Lesson Summary & What To Do Next

Here’s a short summary of the key points in this lesson:

- Integral calculus is concerned with describing the total change in some quantity. In contrast, differential calculus is concerned with small changes.

- An integral is a mathematical operation that intuitively means “adding up lots of small things”.

- Integrals can be performed in two ways; definite or indefinite integrals.

- For a definite integral, you need to specify integration limits. A definite integral will generally give you a number as a result.

- For an indefinite integral, you don’t need specific integration limits. A definite integral will generally give you a function (up to an integration constant) as a result.

- The fundamental theorem of calculus relates the notions of integration and differentiation. This is useful, for example, when solving differential equations in physics.